- Home

- Sarah Lean

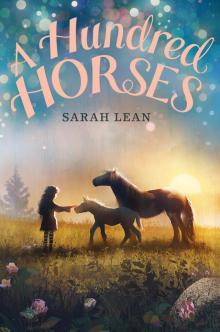

A Hundred Horses

A Hundred Horses Read online

Dedication

For Mum

Contents

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

About the Author

Books by Sarah Lean

Back Ad

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

One

Mom was late picking me up from drama club again. Which meant another twenty minutes of not wanting to be there. There was just me looking through the window as all the other children left. I had one more thing to avoid, and then I could forget what happened earlier.

Me and this boy named Jamie were extras and scenery painters, doing background colors, which was just about all right with us, if we had to be there at all. So I thought if anyone was on my side, it would be Jamie. But he wasn’t. Especially not when he told Mrs. Oliver that I was out back doing dangerous things with the wiring.

Mrs. Oliver blew a fuse and said I should explain myself. I looked at her and took a breath and was about to speak, but then I didn’t know what “explaining myself” meant. You can’t explain yourself. You’re just you. Even though what actually happened wasn’t like me at all. I’d never, ever done anything like that before.

The heat in my face made my eyes sting because I was suddenly thinking about what Mom would say.

“Well?” Mrs. Oliver folded her arms.

“Well, what happened was this,” I said, deciding to tell her the events like a story. “I finished doing the scenery painting, like you said, and Jamie and me had washed the brushes and we were just leaving them to dry and I found those lights . . . you know—the ones you were looking for? And they were in a bag with other things that needed fixing and the plug was missing and I knew how to join them to another set of lights. So I just did it, but I forgot to ask and . . . I didn’t mean to do it.”

“Nell Green, this is so unlike you,” she said. “What were you thinking, playing with such dangerous things?”

Which was silly because it wasn’t dangerous; the lights weren’t even plugged in, so nothing bad was going to happen. And maybe that made me look as if I wasn’t sorry enough.

So I said, “Sorry, Mrs. Oliver, I won’t do it again.”

Mainly I was thinking, Please don’t tell Mom. Which made my face blush and prickle again.

“Who knows what might have happened?” Mrs. Oliver said. “What would your mother say?”

Sometimes you wish people could read your mind.

It didn’t seem to matter that there was now an extralong string of lights for the scenery. Mrs. Oliver didn’t expect an answer, though, because she turned on her heel and clomped across the wooden floor.

So there I was with my face pushed against the window, looking as far down the road as I could to watch out for Mom’s car, hoping Mrs. Oliver wouldn’t see her arrive. But she did, and they discussed the incident through the car window. Now it was an incident, like some great big disaster.

I was belted in my seat, sandwiched between their conversation. Mrs. Oliver said what an unusual skill I had, but that I should be discouraged from messing with electrical things. Surely she meant fixing! Mom agreed instantly and gave me a look that said, How could you?, which was what I mostly wanted to avoid. That look.

“Maybe Nell needs more to do,” Mom said. “Something more challenging to keep her occupied, Mrs. Oliver. A bigger part in the play perhaps?”

One little thing was now turning into a major drama.

Keep quiet, I told myself. Starting Monday there’ll be two weeks of spring vacation with Nana. Mom will be too busy with work and a conference, so there’ll be no after-school clubs, no appointments, no waiting. Just me and Nana relaxing at her house, watching daytime TV, playing cards and computer bingo, safe and quiet. Nana doesn’t drive and she won’t take the bus because you never know who’s sat on the seat before you or where they’ve been, so she can’t take me to rehearsals. Ha! And Mrs. Oliver was bound to forget.

Mom drove away, saying, “Do we need to have a talk?”

“No,” I said. Because her betrayed face said everything.

Two

Waiting again. This time in the car while Mom rushed into the supermarket on the way home. She didn’t leave the keys behind, so I couldn’t open the windows or listen to the radio. I could only hear something rumbling outside and my own sighing.

Waiting makes you sigh. And sighing makes a white patch on the window so you can write “hello” backward.

An old lady with a shopping cart stopped to read my message. So I smiled. But she frowned and walked on. So I wiped the window and watched a giant, thundering yellow crane instead. It turned slowly in the sky, with a big chunk of concrete swinging on a thin wire below it. I didn’t blink for ages, just watching it sway.

Mom came out of the supermarket, shopping bags in both hands, her big black handbag, containing everything anyone could possibly need (and probably a hundred more things as well), weighing down her shoulder. Her phone was crushed between the strap and her ear.

I watch her face for clues and can usually work things out and guess what she’s decided. She has an are-you-listening-carefully face, a don’t-question-me-I-know-what-I’m-doing face, and a slightly smiley making-up-for-what’s-missing face the rest of the time. And I could tell two things by the way her eyes were fixed on me as she walked and talked. The two things I could tell were this: first, the phone call was about me, and second, I didn’t have a choice.

“There’s been a change of plan,” Mom said, swinging the shopping bags into the backseat. “You’re going to Aunt Liv’s for your vacation.”

I wasn’t expecting that.

“But I always stay with Nana. Why have you changed it? Because I touched those stupid lights?”

Whatever she was about to say, she didn’t.

“It has nothing to do with that.”

“Yes, it has. You’ve changed it because of what happened earlier.”

“That’s not it at all. Nana’s had to go up to Leicester on the train to look after her cousin who’s fallen. Auntie Annabel. You remember her?”

Nope. And if you fold your arms, you don’t have to try to remember either.

“The one with the poodle,” Mom said, and I could hear her trying hard not to make this about the incident.

I couldn’t picture Auntie Annabel, just a trembling pinkish poodle and a funny smell of ham.

“I thought you said it died.”

“Yes, but you know who I mean.”

“Why can’t somebody else look after her? Why does it have to be Nana?”

Mom continued as if I’d said nothing.

“The decision’s been made. When we get home, I want you to go up to the attic. There’s a big gray suitcase up there that you’re go

ing to need.”

I noticed we’d completely left out a whole middle bit of the conversation where I could say I don’t want to go. Which is always part of Mom’s master plan. Cut out the annoying middle bit and get to the point, or the next appointment. Never mind what I want.

“Start packing tonight,” she said. “You can do the rest tomorrow when we get back from your math tutor and before swimming club; then I’ll drive you down to Aunt Liv’s on Sunday.”

I don’t like drama club, and I don’t like the math tutor either because her house smells like garlic. My swimming teacher says I swim like a cat, like something that doesn’t want to be in the water.

My life is a list of mostly boring or pointless activities that I didn’t choose, with a car drive and waiting in between. If you practice long enough, you don’t have to care that everything has been taken out of your hands. That’s what moms are for.

“So how was drama club? Apart from—”

“Fine.” I sighed.

When we got home, we ate cold pasta salad out of supermarket cartons. Mom had her phone glued to her head again, and while she was talking, she waved a finger toward the attic door in the hallway ceiling at the top of the stairs.

Three

Our attic was as silent as the moon. Except for my footsteps, which sounded hollow against the boards. The yellow padding in the sloping walls blocked out the sounds of the world. It felt like a place from long ago that had stopped, with its old air and old things we keep because they don’t belong at the dump or in a thrift shop or anywhere else but with us.

I saw the gray suitcase. And I could have just grabbed it and gone straight back downstairs. Instead, I pushed my shoulders back and turned my chin up. I was going to make a stand. And I didn’t mind being up there where the world had paused and nobody could see me or hear me. Just a few minutes of pretending . . .

I imagined telling Mom what I really thought.

Now listen, Mother, I don’t want to go to any stupid clubs. You see, I don’t like them, and I don’t really have any friends at them because I’m not very good at anything and I’m not interested either. Now you want to dump me in a place where I don’t know anyone and I’ll have to do a whole load more things that I don’t care about. And I know how much it upset you and reminded you of Dad, even though you didn’t say . . . but I did actually want to fix those lights. And I really liked doing it.

I didn’t mean to think that last bit. And I knew I’d never be brave enough to say any of those things.

I sat down in the old dust and sighed. That’s when I noticed the tidy pile of cardboard boxes that I was sitting next to. I decided to open the top one.

Inside there was an old Mother’s Day card with crushed tissue flowers on the front and a lined notebook with big, uncertain handwriting and pages and pages of scratchy drawings of a house with five-legged animals in it. At the bottom of the box were clumpy clay models and strange mixed-up creatures made from cardboard, wires, and feathers and buttons. An elephant-giraffe with a long neck and a trunk, a hippo-bird with two clawed legs, and other impossible animals. It’s funny how you can’t remember making these things, even though you must be the same person with the same hands.

I noticed then that the cardboard box had a sticker on it. It said NELL—AGE FOUR. All the boxes had stickers saying my name and my age. Year by year, everything I’d made had been stored in a pile, getting taller every year. I looked inside some more of them. All the other boxes had schoolbooks and reports in them. How come I didn’t make things anymore?

That’s when I saw a brown leather suitcase behind the boxes, lying alone in the shadows under the eaves, forgotten under dust. It was a bit bigger than my school backpack and quite heavy. I heard things shifting inside as I dragged it over by the handle. The leather was worn, the seams grazed, like skin protecting the tender things inside.

There was no sticker on it with my name, but I flicked the latches open anyway.

Inside was like an ancient tomb, full of flat pieces of metal with holes around the edges, narrow strips like silver bones, scattered among ornaments and precious objects. I rummaged through the pieces and found a musical box and sixteen miniature painted horses. I liked the way one fitted in my hand with my fingers under its metal belly and its neck against my thumb. Its galloping legs were frozen in time, its silent eyes wide open. And then I remembered what it was.

Once all the pieces had made a mechanical carousel, almost as big as our coffee table, but taller. I was four when I last saw the brilliance of it, when I last saw the lights and spinning horses. I opened the lined notebook again, the one from when I was four. That’s what the pictures were! Not strange creatures with five legs, but horses with long tails, and they weren’t in a house, they were on a carousel. And then I remembered the buzzing in my skin and brain, the laugh alive in my tummy as I had crouched and gazed at the swirling, whirling carousel.

I held the strings of tiny lights. I could see the filaments inside, as fine as baby hair. I arranged the horses in a circle. I poked the wires from the lights into a black battery cylinder. My hands remembered what to do. The lights burned, white and gold and pink. I turned the handle on the musical box, heard the rusty chimes speed up and come to life. All the fragments lay around me, all the pieces. But I thought the horses kicked; I thought they were spinning beside me, as if they were alive.

“Nell? Can’t you find it?” Mom called. “Do you need me to come up and look?”

I scrambled to scoop all the pieces back up, to hide them away again.

“No! Don’t come up!” I said quickly as I snapped the suitcase shut. “I’ve found it.”

Then I wondered what would be in a box called NELL—AGE ELEVEN. And I remembered why I didn’t make things anymore.

Four

I carried both suitcases down from the attic, without Mom knowing. I hid the secret brown leather one under my bed.

That night I lay waiting for the noises in the house to tell me Mom had stopped turning and was asleep. And I was remembering the carousel and who had made it all. My dad.

Mom said he had always been drawn to lights. It was his business, making spectacular lighting displays for spectacular shows. Then seven years ago he ran away to a place called Las Vegas with someone—called Susie or something—to see the biggest lights of all. We never saw or heard from him again. Mom had said he was probably too dazzled to remember he had responsibilities. She said that we had a new life to live and that now we were free of the pointless dreams of a man who had betrayed us.

Mom couldn’t have known the carousel was in the attic. She would never have let anything of his remain behind. What he didn’t take was put in bags and thrown out. There were no reminders of him. So why was the carousel still here?

And then suddenly I remembered the tin girl, who stood on top of the carousel with her arms out and her head back as if she was about to fly. I remembered waiting for her to turn around, to look at me, as she spun past. Looking at the sky, looking at me.

I got up and crawled under the bed. Quietly I opened the suitcase and turned the metal pieces so they didn’t clatter together, so Mom didn’t hear and wake. But it was too dark, and I couldn’t find the tin girl, couldn’t feel her in there. Where was she?

I got back into bed with one of the horses. The metal warmed in my hand. I could feel the ribs of thick paint brushstrokes.

I turned the horse, felt the smooth curve of its neck, its hooves kicked up in a gallop as it no longer touched the earth. I thought I felt the sway of its mane against my fingertips.

I dreamed. Horses pounded in my heart. Lights brightened, circled, turning faster, spreading wider until I saw her in the middle. The tin girl was real! As tall as me. Her skin reflected the dazzle of the carousel. She lowered her arms and turned her face to me.

“Where am I?” she whispered.

Five

More waiting. A different sort of waiting. Even though the brown leather suitcase stayed shut under

my bed, it was still open in my mind. Now that I’d seen what was in it, now that I’d remembered the tin girl, my hands itched to touch the brightness and life of it. Sunday morning came, and I knew what I had to do.

We left the city and all the things that were familiar to me. We drove toward my mom’s sister, who I couldn’t remember, toward my two cousins, who I’d never met. Mom hadn’t told me until we got in the car that I was going to be staying with two babies as well. When you’re on your way somewhere, it’s too late, even if you want to argue.

“They’re five and seven; they’re not babies,” Mom muttered. She seemed miles away.

“How come I’ve never met them before?”

“People are busy; it’s hard to make time. Families are like that sometimes.”

The polite lady on the GPS told Mom to take the first exit. We turned off onto a narrow road, then onto an even narrower one between some hills.

“What will I be doing?”

Mom glanced over.

“Nell, what’s got into you this last couple of days? Something’s bothering you, so why don’t you just tell me?”

I couldn’t tell her what else I’d been thinking about, like why the carousel Dad made was still in the attic and all the things that it made me wonder about. I was too scared of what she’d say, what she’d think of me. A moment passed. There were potholes and bumps in the road.

“I feel sick,” I said.

“Don’t be silly. The two weeks will pass in no time.”

Which was not what I meant, and anyway, it was wrong. Two weeks takes two weeks. Which is ages.

“No, I mean I really feel sick.”

Mom pulled over, searched her handbag, and fished out a peppermint candy, a bottle of water, and a paper bag—just in case.

I opened the window and leaned my head out. The air smelled cool and clean. I felt the tickle as Mom curved my hair around my ear, a warm patch growing across my shoulder where she laid her hand.

“It’ll be hard for me too,” she said, “being without you.”

I watched her expression, but I couldn’t tell. She kind of looked lost for a minute. Then she drove on, saying we’d be there soon.

A Horse for Angel

A Horse for Angel Harry and Hope

Harry and Hope The Riverbank Otter

The Riverbank Otter A Hundred Horses

A Hundred Horses The Midnight Foxes

The Midnight Foxes Jack Pepper

Jack Pepper The Secret Cat

The Secret Cat The Forever Whale

The Forever Whale