- Home

- Sarah Lean

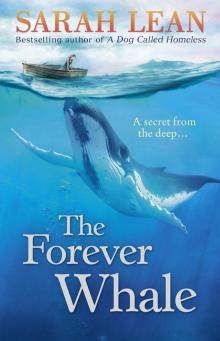

The Forever Whale

The Forever Whale Read online

Praise for Sarah Lean

“Sarah Lean weaves magic and emotion into beautiful stories.”

Cathy Cassidy

“Touching, reflective and lyrical.” Culture supplement,

The Sunday Times

“… beautifully written and moving. A talent to watch.”

The Bookseller

“Sarah Lean’s graceful, miraculous writing will have you weeping one moment and rejoicing the next.”

Katherine Applegate, author of The One and Only Ivan

For Edward, who filmed our home and showed me his point of view … and the cat’s

Table of Contents

Title Page

Praise for Sarah Lean

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Books by Sarah Lean

Copyright

About the Publisher

1.

GRANDAD DRAWS THE OARS INTO THE BOAT as we coast on the glassy water until we nudge into the bank. We both have our fingers over our lips, not to tell each other to be quiet, because we are, but because we think alike. I don’t know what Grandad has seen, I only know to trust him.

“Can you see it, Hannah?” Grandad whispers.

The dappled and striped shadows are barely moving in the golden September evening and I can’t see anything in the jumble of grasses and reeds. I shake my head.

“Keep looking,” Grandad whispers.

I follow his eyes, but it takes me a long while to spot the fawn, curled up and waiting. Its skin is hardly any different from the landscape around it. I can see the glisten of its black nose, but it knows to stay still, to be safe. Once I see it, it stands out a mile.

I whisper, “Is the fawn all right on its own, Grandad?”

He nods his head towards another curve of the bank. A deer is looking at us, anxious because she doesn’t want to draw attention to her fawn, who is separated from her by a channel of water.

Grandad smiles to himself. “Will you stay or will you swim across?” He says it as if he and the deer have a history together. We’ve seen deer here many times, but he’s never said that before.

“I didn’t know deer could swim,” I say, keeping my voice low and soft like his.

“That’s how they came to live on …” Grandad hesitates and looks over his shoulder. His eyebrows are crushed into a frown. He’s looking towards the island in the middle of the huge harbour, even though we can barely see it from here. But I’m not sure why.

“Furze Island?” I ask.

“Furze Island,” he repeats. “A long time ago a herd of deer swam over from the mainland and settled on the island.”

Grandad is still looking far away towards the harbour entrance, maybe for the billow of sails, to see if any broad and magnificent ships have blown in today.

We are quiet for a few minutes until Grandad speaks again. “It’s your turn to row now,” he says.

We change places in the boat. I see him stumble. He must be tired today. Grandad and I have taken a thousand journeys like this out in the quiet inlets of the harbour. Here we are just specks, tiny people marvelling at the changing sea and all the ordinary everyday things. These are my favourite days. I feel the familiar tug in my middle as the oars knock in their sockets and I row, pulling, rolling and lifting like Grandad taught me. The paddles splash like a slow-ticking clock.

“Hannah, I want you to remember something for me,” Grandad says. “Something important, in case I forget.”

I wonder why he would ever forget something important, but I want him to tell me.

“Anything for you,” I say.

“August the eighteenth,” he says. “You’ll remind me, won’t you?”

“That’s a long time away, nearly a year. Are you going somewhere?”

I only ask because I know that Grandad has spent all his life here in Hambourne, working with wood, rowing the inlets with me, and watching from his bedroom window for schooners and square-riggers in the harbour.

Grandad leans against the side of the boat and scratches his white beard and the bristles crackle under his fingernails. His eyes are warm and brown like oiled wood.

“Some journeys need us to travel great distances. But others are closer to home, like today when our eyes see more than what’s in front of us.”

“You mean like finding the fawn in the grass?” I see his face folding like worn origami paper into the peaceful shape I’ve always known.

Grandad slowly puts his gnarly old hand on the bench between us. My hand is still smooth like a map without journeys and I put it on top of his. We pile our hands over each other, his then mine, his then mine, like we always have. He pulls his huge hands out and gathers mine like an apple in his. And, just like always, that feeling is too big to keep inside me and bursts out and makes me laugh.

“Yes, great journeys like this,” he says. “Those great days that live in our memories and make us who we are.”

I’m not sure I exactly understand what he means. I just see something in him and I want to be like him too. Somewhere there in his sun-baked skin is a map of everything that made him who he is.

“Can I come with you on August the eighteenth, Grandad? I want to see what you’ve seen.”

Grandad’s ancient smile fills his cheeks and his eyes and I think of his face as a whole life-full of memories.

“It’s all right here.” His huge hand is over his chest. “The greatest power on earth. Remember, you have to think big, Hannah, and when things are good, think bigger.”

Grandad moved in with us after Grandma died ten years ago. I wasn’t exactly here then, still wriggling and growing into a baby inside my mum, but our home was his before it was mine. Grandad hadn’t liked to live alone and Mum hadn’t wanted him to live alone either. Grandma, who I never met, had done everything for him. She’d pressed his shirts and cooked his tea and put a cushion behind his head when he fell asleep in the chair. Even though he could have done all of these things for himself, she’d thought of him before she did anything.

I’m named after her. She was Hannah Jenkins, I’m Hannah Gray, and in lots of ways I’m like her.

Just then a voice calls across the water. Dad is waiting for us on the slope at Gorbreen slipway. It’s late, he’s saying; he’s telling us to come ashore.

I pull on one oar to steer us in.

Dad steadies Grandad as he climbs out and tells Grandad he should sit in the car, but he stays by the slipway and stares out to the harbour again. Dad and I roll the trailer under the boat. We pull it up the slipway and I leave Dad to hitch it to the car.

I stand beside Grandad and wonder why he’s not getting in the car.

“I think it’s time to put the boat away for the winter, Hannah,” he sa

ys.

I know this means we won’t go out rowing again until next spring.

A curlew is singing, and it’s soft and eerie, filling the bay and my ears.

“Grandad, tell me more about the deer,” I say.

Grandad nods and smiles, but he’s looking at the footprints of seabirds pressed in the soft muddy bank. They’ll be washed away when the tide comes in and draws out again.

“Come on, you two,” Dad calls. “Time to go.”

There’s a long moment before we go, when I see into Grandad’s warm eyes and he says, “I have quite a story I’m saving to tell you about the deer.” He says it quietly so only I hear his deep voice through the curlew’s song.

“Remember August the eighteenth,” he says again. “And one day, I hope you’ll go on the journey and see what I saw.”

2.

“READY FOR SOME TOAST, GRANDAD?”

Grandad likes his toast cooked under the gas grill so it’s dark brown with charcoal around the edge.

“I’ve got it,” I say because Grandad is staring blankly at the kitchen cupboards. I’ve already found the bread knife and cut an extra piece of bread as always.

“Watch the toast a minute,” I say and go outside to feed the birds.

Every morning I still try to do what Grandad and I have always done because it’s helping his memory stay alive. We haven’t been out in the boat again for nearly a year, but there are lots of other everyday things that we’ve always shared. Our early mornings are special, even though things are not exactly the same as they used to be.

Grandad has Alzheimer’s disease. One moment he is as he’s always been, wise and knowing and safe. Sometimes his memory fades like a ship disappearing into a sea mist.

Alzheimer’s usually picks on older people, but it’s not fussy about things like how big or bold a person is, or how important they are to their granddaughter. It’s taking all the things Grandad learned, all the things he saw and heard, all the things he loved. Alzheimer’s is a history thief, stealing his past and our future together.

The hedges shiver with excited twittering as I sprinkle the crusts on the lawn and as soon as I step back the sparrows get busy with the crumbs. I turn the earth with the garden fork that Grandad always leaves there. The robin comes and perches on the fork handle and watches the soil for the wriggle of a worm or centipede. Grandad once said that an ounce of brown and red feathers didn’t seem like much, but it’s the robin’s nature to be fierce like a tiger when it protects its territory. He likes the robin most of all.

I water our sunflowers. They’re taller than me, but the heads are still fresh and green. I can remember Grandad and I crouched in our wellies the first time we grew them. He’d shown me some small black and white striped seeds, shaped like miniature rowing boats.

“See this tiny little package?” he’d said, drawing away one of the seeds with his fingertip. “All it needs is water and the sun and in a few short months it will become a giant. And, when it’s a giant, it will have its own tiny seeds and each one can become a giant too.”

“Like it goes on forever?” I’d said.

“Just like that, only in a new plant.”

We’d pressed our seeds into pots of compost and I waited for them to grow. I hadn’t known what to expect and asked him every day when I came back from school where the giants were. Until I saw them for myself.

But even when the leaves turned dark and the stalks were thick with sap and towered over me, I still had to wait for the new seeds to ripen so that we could store them and then, the following spring, press them into the compost to grow once again.

Grandad follows me outside. I notice he doesn’t have his slippers on, but it doesn’t matter because the June summer ground is dry and warm.

I’ve asked Grandad the same question every day for years, even though I know the answer. I ask him again now: “When will the sunflower seeds be ready?” But this is the first morning he doesn’t reply. I say it for him: “When the hearts are golden,” so that one of us remembers.

Grandad nods towards the hard shadow of the fence in the far corner of our garden where a cat is twitching its tail. He struggles to remember the cat’s name.

“It’s Smokey,” I say, even though I’m sure Grandad will remember in a minute.

“Yes, that’s it,” he says. “We can try and keep the birds safe from him, but Smokey can’t help being a dog.”

I know Grandad meant to say cat not dog. Sometimes the Alzheimer’s makes him muddle things up, but I usually know what he means.

Smokey is a clever grey cat, and I’ve seen him catch baby sparrows before. Even though Mrs Simm gives him plenty of food, Smokey will take a bird if he wants to. I think of Smokey like he’s Alzheimer’s disease, creeping in and stealing things that don’t belong to him.

I hiss and Smokey scrabbles over the fence.

Grandad opens the garage door and he’s trying to untie the tarpaulin over his boat.

“Fair and fine today,” he smiles. “Shall we launch at Gorbreen?”

I don’t remind him we haven’t been in the boat since we put it away at the end of last September. I don’t tell him Dad won’t let us go out any more. “I’ll sort the boat out, Grandad. We could go and see the deer again.” And I lead him away, back into the garden.

“Grandad? Remember you were going to tell me a story?” I say. He doesn’t reply. An ocean of nothing washes into his eyes. “A story about the deer? About a journey?”

This isn’t the first time I’ve asked him. It isn’t the first time I’ve reminded him of the months passing. August 18th is now only eight weeks away.

“Journey?” he says. “Where are we going?”

Suddenly the smoke alarm shrills from the kitchen.

“Grandad, the toast!”

I run back inside. Smoke curls out of the grill and rolls up to the ceiling. I turn off the gas, climb on to the kitchen table and jump up to try to turn the alarm off before anyone else comes down for breakfast, but I’m not tall enough to reach.

Mum runs down the stairs. She stands on a chair and pokes at the alarm with a broom handle until it stops shrieking.

“Watch what Grandad’s doing, please,” Mum whispers as we try to wave the smoke away with tea towels.

“It was just an accident,” I say when Dad comes in.

Dad looks out at Grandad in the garden and I know what he’s thinking.

“It’s my fault,” I say. “I was feeding the birds and chasing Smokey away and watering the sunflowers and I forgot about the breakfast.”

“Sounds like you’ve had a busy morning,” Dad says.

He opens the fridge to get some juice and finds his car keys in there. He takes them out and bounces them up and down in his hand.

“Will you put those boxes by the front door into the car?” Mum says to Dad. “I’ll be along in a minute.” He and Mum share a long look before Mum says to him, “We’ll talk later.”

“Save some energy for school, Hannah,” Dad says on his way out.

Grandad comes into the kitchen. He opens the cupboard under the sink and pulls out a bag of birdseed. He doesn’t say anything about the smoke and the toast, he doesn’t close the cupboard door and the bag of seed is tipping from his hands.

“Grandad,” Mum says, “they’re spilling and going everywhere!” Dots of seed bounce up from the tiled floor around his feet. “Grandad?”

Grandad doesn’t seem to hear her and shuffles back outside, leaving a trail of seeds behind him. I hear the sparrows twittering, waiting for him.

“How is he this morning?” Mum says, sniffing at the bitter smell of burnt toast on her sleeve.

“He’s fine,” I say. “I heard him get up in the night so he’s probably just tired.” Mum frowns. “I can sweep that up,” I say, jumping down and reaching for the broom.

Mum holds on to the handle for a moment. “Hannah …” she says, but I don’t want her to say what everybody in our house has been saying recently, t

hat they’re worried about the way Grandad is behaving.

“He’s fine,” I say again. “I forgot about the toast. It’s my fault.”

Mum sighs a little and says, “Go and help Grandad, love.”

“Mum!” I point to the toast on fire in the cooker behind her.

Mum steps down from the chair and uses the barbecue tongs to pick up the flaming toast and fling it out of the back door, and while she isn’t looking I close the door to the cupboard under the sink because I’ve noticed that there are things inside it that shouldn’t be there.

3.

“WHAT WAS THAT ALL ABOUT?” MY SISTER JODIE says, when Mum has gone to work. “And what’s that disgusting smell?”

I’m on the floor with a brush, but the seeds keep bouncing back out of the dustpan.

“I forgot to watch the toast,” I mutter.

Jodie pretends she doesn’t see me sweep some of the seeds under the doormat.

“Why don’t you just use the toaster like everyone else?” she says, painting gloss on her lips.

I bite my teeth together. “Why can’t Grandad have it how he likes it?”

Jodie doesn’t say anything. She’s more interested in smudging her lips and watching her reflection on the edge of the cooker.

“Why are you putting on lipgloss before you’ve had your breakfast?” I say.

She rolls her eyes and pours some cereal and milk and mutters to herself, “Where’s he put the sugar bowl now?”

Jodie sighs and goes out of the kitchen because the last time the bowl wasn’t by the kettle we eventually found it in a drawer in the sitting room. These things are Alzheimer’s fault, not Grandad’s.

A Horse for Angel

A Horse for Angel Harry and Hope

Harry and Hope The Riverbank Otter

The Riverbank Otter A Hundred Horses

A Hundred Horses The Midnight Foxes

The Midnight Foxes Jack Pepper

Jack Pepper The Secret Cat

The Secret Cat The Forever Whale

The Forever Whale