- Home

- Sarah Lean

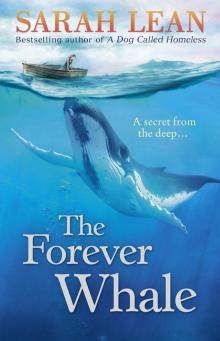

The Forever Whale Page 6

The Forever Whale Read online

Page 6

I shake my head, but she puts a finger to her lips and beckons me into the front garden. Slowly she lifts her stick and jabs it towards a tree. It takes a little while for me to see that she isn’t pointing at a deer though.

Through the ferns and branches of overgrown shrubs I see a red squirrel. The sun is behind its blond ears. It’s frozen, clinging upside down on a branch, its eyes shiny and black and surprised, its tail in a question mark. I hope the camera is pointing in the right direction because I don’t dare let my eyes leave the moment with the rusty squirrel. I move a step forward, but the squirrel whips away and disappears into the tree.

“Did you get a picture that time?” the old lady says.

I nod, “Yes. But it’s a film, not a photograph. I’ll show my sister Jodie,” I say. “She’s doing the Furze Island Project.”

“Whatever are they interfering with now?” she huffs.

“Do you see them all the time?” I ask. “The red squirrels, I mean. Do you know that they’re rare? That’s what Jodie and Adam told me. Adam is my sister’s boyfriend, well, not exactly, but she likes him. They’ve been looking out for seabirds today and they’ll want to know about the red squirrel. But I’m looking for deer.”

She looks directly at me. I wonder if all old people have knowing eyes like that. I wonder if Grandma had.

“Will that deer come back?”

“She will,” the old lady says. “But I doubt she’ll come back today. Deer are shy, they prefer to hide away from people.”

“Did she swim over from the mainland?”

She looks startled for a moment. “No, this one has always lived here.”

“She’s not shy with you.”

“No, because …” She’s still watching me. She has a frown buried deeply around her eyes. It looks like it’s been there a long time. “What is the film for?”

I don’t know why I think it’s all right to tell her. She lives on this island. It feels like I can say it easier here because it’s separate from home and people I know. She doesn’t know Grandad, so she won’t be disappointed or uncomfortable or compare him with how he used to be. She’ll only know him from what I tell her now.

“My grandad’s got Alzheimer’s and he’s forgetting everything and now he’s forgotten me. I’m looking for things to film for him, to help him remember. My mum told me he used to go and see the deer with my grandma. He came here too.”

“Dusk and dawn, East Beach,” she says. “That’s where the deer go.”

I start to say nobody is allowed on the island at those times of the day, but she interrupts and says, “Yes, I know you won’t be able to see them there.”

I smile. “Can I come back here another day?”

“Yes,” she says, “but quietly next time.”

20.

I ASK LINUS TO COME WITH ME OUT ON GRANDAD’S boat that evening. We have our life jackets and Dad says it will have to be a short trip because, although the long summer night is light, Dad didn’t get home from work very early.

“Stay in sight,” Dad calls from Gorbreen slipway.

I’ve never been out in Grandad’s boat with anyone else but Grandad. It’s a new experience. I teach Linus how to row, but we spend half the time turning in circles and bumping into banks. It makes the video camera judder each time we do.

“What exactly are you looking for?” Linus says. His hair is extra curly today and he has to keep pushing it back from his forehead. He’s sweaty and I know it’s hard rowing, but only if you’re not used to it.

I don’t want to say that I’m looking for Grandad and Grandma because that sounds ridiculous. But it is what I’m looking for. I try to make the words say what I mean without sounding daft.

“I’m not really sure yet. I keep thinking that I’m going to find something, but I don’t know exactly what it is. I’m kind of looking for a bright memory of Grandad’s.”

Linus screws up his nose. “Memories aren’t outside.”

I try another way. “These are the facts I’ve got so far. Grandad and Grandma knew each other when they were children. Grandad had a boat all his life and Mum told me Grandma had a soft spot for deer. So they might have come out here in a boat and seen some deer. Last year when I was out in the boat with Grandad we saw a deer and he talked like it was kind of familiar. So I’m trying to recreate his memory in a film. And then hopefully he will remember something important he wanted to tell me.”

Linus shrugs.

It sounds logical and simple. But why would that be a special journey that Grandad wanted to take me on? We’ve rowed out here a thousand times. Why didn’t he tell anyone about it before? And it doesn’t seem to have anything to do with a whale. I don’t know how to make all the pieces fit together. Not yet.

“Just keep your eyes open for deer,” I say.

“Like your grandad and grandma did,” Linus says, as if he’s trying to convince himself of what I’m doing.

There’s rustling as we bump into another bank and we see the dark stripe of tails ticking against white rumps as deer scatter into the long grass.

Linus laughs. “Like us,” he whispers because I have my finger over my lips. A curlew sings and my mouth can’t help smiling. For a moment I think he might be right. I wonder if one evening in Grandma and Grandad’s past might be exactly the same as the one we’re having now.

21.

THE GATE TO THE OLD LADY’S HOUSE IS AJAR, but she isn’t in the front garden. Her front door is open and I go inside. I can’t call out because if the deer is here I don’t want to scare her away. My video camera is on.

There’s a closed door on one side of me, an open one on the other. The kitchen is grey, camouflaged with dust and dirt. There are rows of tins with beetles and frilly woodlice clambering over them; thick webs spotted with flies curve in the corners. All the colour is in the white bread on the sink, orange peanuts on the windowsills, handfuls of fresh grass and wild flowers on a chair.

The hallway opens up. I see unopened letters yellowing on a table, addressed to Miss E Bennett.

Straight ahead another door is ajar into a brighter room.

Miss Bennett is in her splintered straw hat, hunched in a wicker chair outside the French windows, but as I creep in I’m distracted by a wall of framed photographs. I look closer. They’re like a crowd of people standing shoulder to shoulder and on top of each other and beside each other, blurred in a fuzz of dust. The photographs are shades of brown or grey and all the people look out from behind the glass, like an audience. I think about Grandad as if he’s a photograph and he can’t speak to tell me what it’s like in there, inside the frame and behind the glass.

“Hello,” I whisper, “hello, hello, hello,” to all of the people in the pictures because I’m thinking that they’re like Grandad and I don’t mind too much that they can’t answer me.

“My name is Hannah,” I say to them. “I’m named after my grandma who died before I was born.

“You look nice,” I say to the old-fashioned black and white picture of a girl a bit older than Jodie, who is in a rowing boat out at sea with Furze Island in the background. The girl is sheltering her eyes from the sun and her hand holds back her wavy hair. She is smiling and I wonder if it counts, that the smile she gave then could also be for whoever looks at her now. A camera is hanging from a strap around her neck.

“That’s what I’m doing,” I whisper to the girl in the picture. “Sort of anyway.”

I’m not sure if they had video cameras back then. I zoom into her face; I wonder about the photographs she’s taken, why she took them and if she was on a journey like me.

“What did you want to take photos of?” I whisper.

“Things not to be forgotten,” Miss Bennett says.

I hadn’t noticed she’d come in. She is as grey as the girl in the old photograph, still squinting now; she has the same roundish face only now it is scored with wrinkles.

“That’s you, isn’t it?” I say. “How old were you back

then?”

It takes her a moment to say, “Nineteen forty-two … so I would have been seventeen.”

“What don’t you want to forget?” It feels like a really important question because that’s what I’m doing. Trying to make sure something isn’t forgotten.

She turns away before she finishes speaking. “The person who took that photograph.”

I hadn’t expected that.

Miss Bennett puts a finger to her lips. She is eighty-eight years old and her hands are like fossils. She leads me outside. The deer is in her back garden.

“That’s Fern,” Miss Bennett says softly. “She comes most days, just like her mother did and her grandmother and great-grandmother before her.”

My eyes are wide. She’s known the deer for a long, long time! I think I’ve found another path to Grandad. She might know something about what happened to them in the war which might help me find out what Grandma and Grandad have to do with the deer. I have a million questions, but I know to be quiet for now.

Fern has ears like a mouse, black eyes and white spots on her golden sides and she holds her head up and looks at me as if to say, I’m not sure about you.

There are two wicker chairs on the patio. I walk very slowly and put the video camera on the small cane table between the chairs and check Fern is in the picture.

“Do you know what happened to the deer in the war?”

Miss Bennett shakes her head. Ancient sadness is in her eyes. “There was one terrible, terrible night,” she murmurs.

She thumps across the garden with her walking stick. Fern watches her, but doesn’t run away. I realise she’s used to the sounds Miss Bennett makes, but not mine.

Miss Bennett looks out over the cliff top through the break in the wall. I follow her quietly and stand beside her and see where her eyes are looking, through the harbour entrance and away to the horizon. She pokes with her stick at the tumble of bricks around her feet. Fern is beside her now and Miss Bennett is talking as if to the deer. “The war took many things, didn’t it?”

I think of all those photographs she has, her family from the past. I wonder how many of them didn’t come back from the war. I wonder about the deer. Did something happen to them in the war? Something Grandad knows about too?

I wish I hadn’t made Miss Bennett remember something that makes her so unhappy. The war was such a long time ago, but I think her memories are so strong that she still feels the sadness now.

“Sorry,” I say.

“For what?” she says.

I daren’t say anything else.

She breathes deeply and I copy her. I smell the briny sea in the air. I feel how the outside rushes inside my chest and blows away everything uncomfortable. I taste it in my mouth. I hope Miss Bennett’s bad memory will be carried out to sea with her breath.

“I don’t think my grandad had a bad memory of the deer,” I say. “He doesn’t think like that. I don’t think he would have wanted me to know about something sad. He always sees the good in things.”

Her hand loosens around the handle of her stick. She strokes Fern. “Only one good thing did survive from the island that night.”

The atmosphere between us feels wrong, and I don’t want Miss Bennett to still hurt, so I try to change the subject.

“Do you think the sea might be the greatest power on earth?” I ask.

“No,” she says. “War was.”

And I think she’s still thinking of something terrible that happened then.

22.

OTHER LOST GRANDADS AND GRANDMAS ARE IN the television room at East Harbour Care Home, their necks drooping; their distant eyes scare me a bit. And then I think that there must be lots of other grandchildren like Linus and me.

Mark, a physiotherapist who is helping Grandad with his movement, meets us out in the hallway.

“How is he?” Mum asks.

“Fine,” Mark smiles. He’s saying what I always used to say and I guess that means he’s trying to protect us, or trying to hide something. He nods towards the video camera and speaks to me. “As far as his memory and mood go, the more you can do to help him, the better. It’s a bit like he’s stranded in a small place, but we can help by reaching out to him.”

“Like on an island?” I say.

“That’s it,” Mark says, surprised. “Just like that.”

All the cheerfulness and gentleness are still missing from Grandad’s face. Now he looks like everyone else in the TV room, like anybody’s grandad. I hate that I even think that.

It takes a little while of everyone chatting and telling Grandad lots of times that it’s us before the ocean of nothing clears a little from his eyes. He reaches for my hand. It looks like the same hand it has always been. But how can such a big strong hand feel so papery and fragile?

“I’ve got something to show you,” I say.

He babbles something. It sounds like he’s having a conversation with someone from when he worked in the boatyard, but none of us are quite sure what it’s about. Jodie and I look each other in the eye, to make each other braver.

Jodie puts her laptop on Grandad’s lap and we link it to the video camera. Jodie helped me edit the film so that all the boring bits (like Josh and the sausage and beans) got cut out, and all the good bits (like the harbour and the deer) follow each other like a story. I talk to Grandad while we watch and describe what is happening in my film: our house, Linus and his scooter on Southbrook Hill, Mum talking and the trip on the ferry to the island. Grandad’s lips tremble and I think he tries to smile and every now and then his eyes brighten.

“I think he’s seeing things he remembers,” I say.

Somewhere, shining through his slumped body and drooping mouth, we can all see a little bit of Grandad as he used to be. And it only takes a tiny bit of remembering him like he was to make us all feel good.

“Hannah, I think you’ve found your talent here,” Dad says, while we watch the film.

“She has, hasn’t she?” Mum smiles widely. “This is a beautiful film for all of us. What a great thing to keep for our future too.”

“Even Grandad’s smiling,” Jodie says.

“Imagine if someone was grumpy and miserable their whole life,” Mum says, “how little the family would be left with.”

“Like Miss Bennett,” I say.

“Who’s Miss Bennett?” Dad says.

“She’s a very old lady who lives on Furze Island. I think she’s been unhappy most of her life. Except when she was a girl because she looked happy in a photograph when she was seventeen.”

Mum and Dad look at each other, a question in their eyebrows.

“How do you know her?” Dad says.

“I visited her,” I say and then realise what that means.

“Jodie?” Mum asks and Jodie is gritting her teeth.

“I didn’t know! I can’t look after Hannah the whole time,” Jodie says. “I’ve got important things to do.”

“With that boy Adam?” Mum says.

“Who’s Adam?” Dad snaps.

And then there’s a whole discussion, which is nearly a row, about Jodie’s responsibilities and me not going off on my own into a house with someone they don’t know. It’s only then, with the film still running and nobody talking to Grandad, that I suddenly see the change and hear the soft groan that comes from him. And we all look because none of the other things matter except that Grandad might be trying to remember us.

His smile is gathering; he laughs. And then he says it. It isn’t clear, but I’m sure I hear right. “The whale,” he says, as if there’s something in front of him now. “It was a whale.” He reaches his arms out as if he is trying to hold on to something.

I press pause on the camera and there on the film is what I recorded at Miss Bennett’s house. Fern the deer. But how can Fern remind him of a whale? Is it something else earlier in the film? Is it just luck that at this moment he happens to remember the whale? But Grandad babbles and mutters and we can’t work out what he’

s saying. He draws his arms into himself, as if he’s holding someone small in his arms, but there’s nothing there. “There, there,” he says. “Safe now.”

On the way home nobody feels like I do, that Grandad is still trying to tell me about a whale. They all keep saying that maybe Grandad is getting confused and that he’s remembering saying it before he had the stroke, because there’s nothing on the film to do with a whale. That’s not what I think at all. I think the whale is becoming more important than ever. But Dad is mostly stressed about me going to Miss Bennett’s.

“We don’t know her,” he says.

“But she’s really old and sad and lonely,” I say, trying to make him sympathise.

“That’s as may be, but it’s not your responsibility to look after the old people of this world,” Dad says. “I want you to stay with Jodie from now on.”

Jodie rolls her eyes.

“But Grandad saw something on the film and it might have been at Miss Bennett’s house,” I say. “It might be the one important thing that he wanted to tell me.” And I want to know more than ever.

“Hannah, we all want Grandad to get better. There are other things you can film. We’d all like to hang on to what we think will help his memory, but we have to face the fact that Alzheimer’s makes him say and do things he wouldn’t normally.”

Mum sighs. “His mobility is improving. We all need a little hope.”

“There’s hope and there’s reality,” Dad mutters.

Grandad’s memories are real. I’m sure of it. There are more paths now, more things that are leading me somewhere. Closer to the whale?

23.

MISS BENNETT HAS SAD MEMORIES OF THE WAR. I think about that a lot. If I keep asking her about the war and the deer, I’m going to make her unhappy. I need to find something good for her to talk about. I need to find something good and make it bigger, because I’m hoping to find another path to Grandad.

A Horse for Angel

A Horse for Angel Harry and Hope

Harry and Hope The Riverbank Otter

The Riverbank Otter A Hundred Horses

A Hundred Horses The Midnight Foxes

The Midnight Foxes Jack Pepper

Jack Pepper The Secret Cat

The Secret Cat The Forever Whale

The Forever Whale