- Home

- Sarah Lean

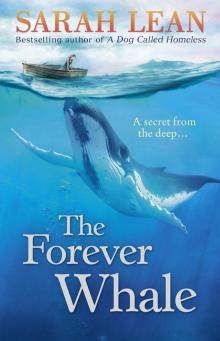

The Forever Whale Page 3

The Forever Whale Read online

Page 3

Mum shakes her head. “I don’t know if he knew it was me,” she says quietly. “I don’t think he recognised either of us.”

I push between Mum and Dad on the sofa, the only space I can see that feels safe.

“Can we visit him?” Jodie says, squeezing on the other side of Mum.

“Not just yet,” Dad says.

Mum touches Dad’s arm. “He’s very confused and weak at the moment,” she says. “I’ll go in tomorrow to check how he is and let you all know. Then we’ll see when he’s up to having more visitors.”

We know that nobody gets better from Alzheimer’s, but the doctor said it’s possible Grandad can recover from some of the symptoms of the stroke. But the way Mum described him sounded all wrong, like it was someone else in hospital, not my grandad. I keep thinking he’s still here, somewhere, only I can’t find him.

I get up from the sofa.

“I don’t want to see him in hospital,” I say. “But when he comes home, there’s something we have to do.”

“What’s that?” asks Dad.

They all look at me and I’m not sure now how to say what I’m thinking. Our journeys were about being together and discovering things, and seeing the world in front of us with bright eyes and open ears. I was going to take him out in the boat again. We wouldn’t go far – we’d stay in the inlets and quiet harbour waters. Because I’m sure, if we did, he’d remember everything he wanted to tell me.

“We’re going to take a journey together,” I say, but don’t wait for them to ask questions because I can’t explain anything more. How can I tell them that I think we’re going to find a whale?

I go out to the kitchen and rummage through the cupboards until I find the spray gun. I fill the bottle with cold water from the tap. I go out to the garden and shout into the night shadows, “Just you wait until Grandad gets back, Smokey! I know it was you that killed the robin.”

8.

“DID YOU THINK SOMETHING WAS WRONG WITH Grandad yesterday morning?” Jodie says when I meet her on the quay the next day on the way home from school.

I feel guilty because I’ve been trying to cover up some of the things he did, and maybe I shouldn’t have done that.

“Yes, but most of the time he was fine,” I say. It’s an effort to lie and makes my stomach hurt. “I wanted him to be fine,” I say quietly.

Jodie knows I feel bad and I can trust her not to make me feel worse.

We stare at the statue of the faceless people.

“It’s weird how they didn’t give them faces,” Jodie says.

“Mrs Gooch said it’s so we can all see something of ourselves in them.”

Jodie pulls a face and I know what she’s thinking. Nobody’s faces are the same – they have different shapes and colours and ways that they are put together.

“It’s not like a mirror or anything,” I say. “It’s just that it’s supposed to remind us of things like being safe or rescued or people we know, something like that.”

I see Grandad and me in the statue. He’s the big brave figure in the boat reaching for the small one, to carry them safely back to shore.

“What’s the greatest power on earth, Jodie?”

“That sounds like something Grandad would say.”

“It is something he said, ages ago. He was going to tell me a story … about a journey.”

Jodie screws up her face and tips her head to the side. “Maybe the greatest power on earth is Art,” she says, taking a long look at the statue. “But not this bit of art. It’s weird.”

I notice Jodie has black eyeliner and mascara and her lips are glossy and pink.

“Have you got a boyfriend?” I say.

“No!” she says, far too strongly.

“Thought so. You don’t normally wear so much make-up. What’s your boyfriend’s name?”

“He’s not my boyfriend,” she says, “I just like him.”

“How much?”

Jodie’s painted eyes open wider.

“Loads,” she says which makes us smile, but our faces drop again straight away. Even that can’t stop us thinking about Grandad.

We walk along the quay to Hambourne slipway.

“Is this where you found Grandad?” Jodie says. I nod. “What was he doing here?”

Behind the slipway and across the other side of the road is a fairly new row of flats. I can’t remember what was there before it became a building site, before they built the flats. I don’t know if that has anything to do with why he came here.

Three red inflatable boats, with big engines on the back, are moored at the slipway. Divers are unpacking air tanks and crates on to the quayside. There’s a journalist and a cameraman there and they are interviewing another man nearby.

“I wonder what they’ve been doing,” Jodie says.

“It must be important because they’re filming it.”

“Were the divers here yesterday? Maybe Grandad heard something about it on the radio and came to see.”

I look up at Jodie. “I didn’t notice.”

“Maybe he was lost.” Jodie sighs. “You must have been really scared.”

I was, because of what might have happened. Grandad could have fallen in the sea. My lips tremble with the cold thought that things could have been even worse. And because she’s Jodie she puts her arm out so I can snuggle in.

We watch the gulping tide below at the bottom of the steps and the three long red boats rocking as the divers take the equipment out. The sky is grey and it makes the sea grey and blank too and I wonder if that’s what it’s like for Grandad right now. Just looking at lots of the same nothing. I want to be with him, and I don’t. I want to be with Grandad as he was before Alzheimer’s took him away.

I try to listen to what the journalist is saying. I can’t hear the man who’s being interviewed, but he waves towards the harbour and then folds his arms and nods.

“We could ask them,” Jodie says. “They might have seen Grandad here yesterday.”

I shake my head. When someone has Alzheimer’s, it feels like a private thing.

“Is your boyfriend from school?” I say to Jodie to change the subject because my eyes keep falling back on the greyness below us.

“He might be,” Jodie smiles, and I know she feels the same and would really rather talk about him, and it’ll be much easier than what we’re thinking about. “He’s doing the Furze Island Project, so I’ll get to see him most of the summer.”

I pretend I have a microphone like the journalist and make it sound like I’m interviewing her.

“Today, I’m talking to a girl called Jodie Gray who is fifteen and is wearing lipgloss and she’s going to tell us lots of interesting things. So, Jodie, what’s the Furze Island Project?”

Jodie coughs and smile, as if there really is a camera filming her, and puts on a newsreader’s voice.

“The Furze Island Project is run by a group of volunteers from our school. You have to be in Year Ten or Eleven and enjoy being outdoors and interested in nature conservation. The volunteers are going to clean the beach and clear some gorse, and look out for wildlife and make a record of what’s there.”

“Very interesting,” I say, thinking of another question. “And is it just girls or are there boys doing it as well?”

Jodie gives me a look. “Both.” Then she twinkles, “Including a very handsome boy called Adam.”

I notice Jodie’s cheeks don’t need blusher because they’re pink anyway.

“I think you love Adam,” I say.

“Hannah!” Jodie says, nudging me. I make my voice deeper and more serious.

“Thank you, Jodie,” I say. I hold out the pretend microphone to her again. “And what sort of wildlife are you looking for?”

“Any,” she says. “Whatever we see we’ll make a record of, but we’ve especially got to keep an eye out for red squirrels, lizards, whales—”

“Whales?” I say, startled.

She shrugs. “Or dolphins, anything unusual.”

> “No, but you said whales.”

“I know. Whales – what’s wrong with saying that?” Jodie has her shoulders up and her palms turned out like I’m being silly. “We won’t see whales, they don’t come here. I’m just saying that’s what I was told to look out for. Anything, including whales.”

I reach back in time, and I hear Grandad telling me, Let’s see if we can find that whale.

I wish I’d not gone to school yesterday because then maybe he wouldn’t have had the stroke, I could have kept him safe. Imagining these things makes my mouth dry. I am breathing too fast.

“Where can you find whales?”

Jodie shakes her head. “What do you mean?”

“Think,” I say. “Where could Grandad have gone and seen a whale?”

She shrugs. “Why? What’s wrong?”

“I think we were going on a journey in the summer holidays. He said something about a whale. Just before he had the stroke … he said to remember August the eighteenth for him.” I try to take a deep breath because all of a sudden I can’t remember how to breathe and my lungs won’t fill. “I should have stayed at home with him.”

Jodie curls her arm round me again. She whispers, “Shh, it’s not your fault; nobody expects you to look after him,” and then a long minute passes before my lungs remember what to do.

“Can we go home now?” I say. “I need to find out everything I can about whales for when Grandad comes out of hospital.”

I’m going to look on the computer to see if I can work out where Grandad wants to take me. And, if Grandad can’t tell me what’s important, I’ll find out for myself.

9.

WHEN MUM COMES HOME, SHE SAYS, “WHAT ARE you doing here all by yourself, Hannah? Where’s Jodie, she’s supposed to stay with you after school?”

“She had to meet up with her friends from the Furze Island Project.”

Mum looks around at the floor. She crouches beside me and holds my shoulders.

“What have you been doing?” she says.

Memories of the past are still circling in my mind, the things that Grandad had said: Remember August the eighteenth for me; the night I’d been sick when he talked of Grandma, Something great put us together, bound us together forever, and it will never be undone; in the boat when we saw the deer, Will you stay or will you swim across?; yesterday morning, Let’s see if we can find that whale.

I’m shocked at what I now see around me, the mess I’ve left from searching through cupboards and drawers, through old papers and photographs and passports. I thought I’d find something from Grandad’s past that I could hold on to until he came home, something real in my hands, because I can’t think of a place in the future where Grandad and I can be together.

“I’ve been looking for a whale.”

10.

AT DINNERTIME I GIVE DAD A LIST OF COUNTRIES where you can see a whale. He keeps chewing and slides the piece of paper across to Mum. “I don’t think Grandad’s ever been on an aeroplane,” he says. “I don’t see how he could have gone to any of these places.”

“He didn’t come with us when we went on holiday to Spain either,” Mum says. “What about Scotland?”

Dad doesn’t look convinced. “When did he go to Scotland? Grandad’s not been much of a traveller.”

“It’s probably a memory from when he was young,” I say. People with Alzheimer’s often remember things from a long time ago.

I realise none of us could have known him then. Nobody can think of anything. We are blank and useless. He must have gone somewhere to see a whale before. Why else would he say we were going to find one?

“What’s the greatest power on earth?” I ask.

“Do you mean like volcanoes or earthquakes?” Dad says.

“Maybe, I don’t know.”

“Is this something Grandad said?” Mum asks. “One of his big ideas?”

I nod.

“What about family bonds?” Mum suggests.

I like that, but then I feel the heaviness in my stomach because of who is missing. I’m not sure what it has to do with a whale though.

Just then Jodie bursts in through the front door, takes her plate out of the oven and comes to the table. She starts eating before she’s taken off her jacket or sat down.

“What?” she says because Dad is staring at her.

“You were supposed to be here with Hannah,” Dad says.

Jodie draws a sharp breath. “I forgot!”

“Forgot?” Dad says, shaking his head, which makes us all think again.

“Look, we’re relying on you—” Dad begins.

“I know, I know,” Jodie interrupts. “I’m sorry, I won’t do it again.”

Mum raises her eyebrows at Jodie, but I’m thinking it’s not fair to blame her.

“I’ll remind her,” I say.

Jodie looks at me while she’s trying to eat and take her jacket off at the same time. “Guess what?”

Dad tells her to sit down properly.

“Have you found out something about a whale?” I ask.

She hesitates, the fork near her mouth, and blinks slowly.

“No, but you know those divers we saw earlier, Hannah?” she says. “They’ve found something on the harbour seabed.”

I put down my knife and fork. I wonder what they’ve found.

11.

THREE WEEKS PASS BEFORE MUM AND DAD SAY Grandad is ready for Jodie and me to visit. I still don’t want to go. I don’t want to see him until he’s better and back with us. And I’m scared of what I’ll find in the hospital bed. A grandad who doesn’t know us.

I write a kind of diary for Grandad while I’m afraid to go and see him, while I wait for him to come back home. I tell him about the birds and the sunflowers. I try to make all the good things sound bigger than they are, but it’s hard to find anything that stands out without him here. I don’t say that I think Smokey’s been again, that there are fewer sparrows than before.

I tell Mum and Dad that I have to revise for a test at school and they don’t question why we’re having a test right at the end of term, but drop me off at Megan’s instead.

Megan talks non-stop about the summer holidays and going to Tenerife. She talks about her new swimming costume and sunglasses and other small things.

I ask her what she knows about whales. She shrugs. “They’re big,” she says. I still haven’t told any of my friends that Grandad has Alzheimer’s. I don’t think they’ll understand. We both avoid talking about what happened to Grandad near Hambourne slipway, but I ask her if she knows what used to be there, before they built the new flats. She can’t remember either. I don’t think it’s just Alzheimer’s that makes people forget.

I decide that when Grandad comes home I’ll have to wait for the moments when he is bright and here with us. I’ll wait for the ocean of nothing to clear from his eyes and we’ll plan our journey to find a whale. I need something to look forward to.

Dad, Mum and Jodie pick me up after their visit to the hospital.

“Is he better?” I ask.

I see in Jodie’s face that she’s disappointed, like she’d arranged to meet someone and they weren’t there. I think she’s hoped too much, but now she’s giving up. “He didn’t know me,” she says.

I stretch the seat belt out and lean forward.

“He has to come home, doesn’t he, Mum?” I say. “And then he’ll have all the familiar things around him. That will help him remember us.”

We pull up outside our house. Nobody undoes their seat belt or gets out. Mum touches Dad’s arm as if to stop him from speaking.

“She needs to know,” he says.

There is an ocean of silence before Dad’s words smack through the air.

“Grandad isn’t coming home.”

“What do you mean?”

“He’s being moved into a unit where they can look after him.”

“A unit? What’s a unit?” I hear the shriek in my voice. I hadn’t meant it to come out lik

e that just as Dad hadn’t meant to hurt me with what he said.

“It’s a care home,” Mum says, frowning at Dad. “A place where they specialise in looking after people with Alzheimer’s disease.”

“How long?” I say.

“It’s the best place for him,” Dad says. This time Dad reaches for Mum’s hand. “We all agreed.”

“Home is the best place for him,” I say. “How long?”

“We’re sorry, Hannah,” Dad says, “but he’s going to stay there now for good.”

No. I can’t believe that they have made that decision for Grandad. How could they? I slam the car door and run through the house, straight to the back door. Smokey, the thieving cat, is sitting on our lawn. I creep out of the back door and turn on the tap and point the hosepipe at him.

“You’re the one that’s not wanted here!” I yell.

Smokey leaps up on to the fence, but when I follow him with the spray the water stops to a dribble. Dad has turned the tap off.

Mum follows Dad into the garden. She takes the hose from me.

“There is something we can do,” Mum says. “The people we saw from the care home said we should try to bring some memories from home to take to him, especially things from his past.”

“Come here,” Dad says and wraps me into his belly. “I’m sorry I had to tell you. We all need to know where we are.”

But I feel more lost than ever.

12.

EAST HARBOUR CARE HOME IS A WIDE BUILDING up on a cliff with a view out to sea. I go with the family to visit Grandad when he’s been moved there. But it’s not like our home. It smells of disinfectant and mashed potato. We wait at reception and I look back through the doors. At least he can see the sea from here.

We pass other rooms in the hallway; they all have the same carpet and furniture, new and plain, as if somebody furnished this place without thinking how different all the people would be.

Grandad’s outside is familiar, his tall broad shoulders, his long legs, his wide sandpaper hands. But the more his memory vanishes, the more something inside of him shrinks as well. It’s as if all of his unique Grandad-ness has been stolen right out of his body by the stroke, as if whatever held him together before is crumbling. He’s sitting differently; his shoulders curve and sag. I don’t think he can sit upright because he’s tall and it’s not his chair with the soft bow in the seat and the high back and the varnish wearing off the arms. There’s nothing of us here either, none of our furniture or our things.

A Horse for Angel

A Horse for Angel Harry and Hope

Harry and Hope The Riverbank Otter

The Riverbank Otter A Hundred Horses

A Hundred Horses The Midnight Foxes

The Midnight Foxes Jack Pepper

Jack Pepper The Secret Cat

The Secret Cat The Forever Whale

The Forever Whale