- Home

- Sarah Lean

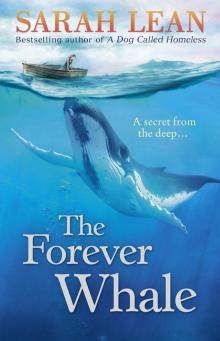

The Forever Whale Page 4

The Forever Whale Read online

Page 4

“Hello, Grandad,” I say and it’s hard saying those words because I don’t want to feel like a visitor, someone who calls in now and then.

He doesn’t recognise me.

I give him a bar of chocolate, but he seems to have forgotten the sweetness of that too. I want him to know that I didn’t agree to him being here. Mum and Dad made that decision. But I don’t know how to tell him so he’ll remember. What if he only keeps a memory of us abandoning him?

“It’s me, Hannah.” My voice wobbles. “Your grandaughter.” It’s like I have to start all over again with him.

“He’s trying to remember,” Mum says, “and you know that if he possibly could, he’d find a way.”

Dad reads the newspaper out loud, but Grandad doesn’t seem interested. The diary isn’t working; neither do the old photographs that Mum shows him. She’s brought in a framed family photo of us all, but there’s nowhere to hang it. Dad says he’ll have a word about that. I try and find somewhere for it to lean, but there are gaps between the furniture and walls, and no space on the surfaces, so I have to put it in a drawer and that nearly takes all my breath away again so I leave the drawer open.

There has to be another way to help him.

I kneel down and put my hand on Grandad’s knee and wait for him to pile his hands over mine. His eyes brighten and I know he feels me touch him, but his hands stay where they are.

“Grandad?” I say. “I had a rubbish day at school.”

Every day after school, Grandad used to ask me to tell him what had happened that day. Sometimes it was what I learned in geography or history, sometimes it was about my friends or other people, sometimes things I liked, what annoyed me or made me sad, or things I was afraid of. Grandad’s beard would crackle as he rubbed his chin and listened. It was like pouring out my day and giving it to him. If things made me unhappy, he’d always ask me to look at things another way.

“I got in a mood with Megan because she was talking about going on holiday and I’m not going anywhere.” Megan’s holiday reminded me that Grandad and I wouldn’t be able to take a journey together now.

I wait for him to ask his brilliant big questions that make all the bad things sound small and insignificant, for the horrible feelings to vanish, for all the good things to shine.

“Grandad?” I ask him again to come back to us. “It’s all rubbish without you.”

It’s strange how our memories suddenly bring us something. I remember him saying, You have to think big, Hannah, and when things are good, think bigger.

I don’t know what happens then, but when I look up for a moment I see Grandad as I always used to. He is still a giant in my memory. I feel him sheltering me, like he always has. He must still be here. And if he is then we must also be in there somewhere.

And then I think, what if I take the journey on my own and find the whale for him?

13.

THE HOLIDAYS BEGIN. IN THE SUMMER SEASON tourists come to Hambourne, to the pottery gift shop that Mum and Dad open for long hours near the quay. Mum tells Jodie she will have to look after me because neither Mum nor Dad can take time off. She says that some people think it’s a burden having old folk around, but Grandad had made life easier for everyone.

“But I’ll be doing the Furze Island Project from next week,” Jodie sulks.

“You’ll have to apologise and pull out,” Mum says.

“But I’m going to be with my friends!”

She thinks that’s a good enough reason, but Mum and Dad have told her often, like Mum does now, “The world doesn’t revolve around your social life, Jodie.”

“She wants to be with Adam,” I say.

“Who’s Adam?” Mum says.

Jodie drops her shoulders and makes a big huffy sigh. “Nobody,” she says, glaring at me.

“Well, he must be somebody,” Mum says.

“He’s doing the Furze Island Project,” Jodie says through her teeth. “And I want to do it too!”

Mum sighs; she wants the argument over.

“Do you remember when we went to Furze Island, Hannah?” Mum says. “Grandad was with us.”

“Me?” I say, but I don’t remember. Furze Island is in the middle of the harbour and is only open to tourists for the sunny months of the year.

“I’m not sure where Jodie was that day,” Mum says.

“Why haven’t we been back?” I say.

Mum shakes her head and shrugs. “Too busy working probably.”

It’s funny how we hardly ever seem to visit some of the things on our doorstep. They’re so familiar and, even though I can see the island every day from our garden or Grandad’s bedroom, I hardly notice that it’s there at all.

“Mum?” Jodie says. “We were discussing me!”

Maybe it’s because I’ve seen those journalists and cameramen recently, but I think about making a film. I think of recording the things that Grandad has shared with us in his life, something that will help him remember us when he watches it.

“Why don’t I go with Jodie instead?” I say.

Mum raises her eyebrows. “Now that sounds like a good plan. Jodie?”

“But, Mum!” Jodie whines.

“Jodie, would you just do as you’re asked for a change? If Grandad was well then Hannah could stay at home, but you know Dad and I have to work and you need to do your fair share.”

Any time Jodie gets in a mood Mum and Dad remind her that Grandad is the reason we should stop arguing. It makes everything sound like it’s Grandad’s fault though.

“Could we buy a video camera?” I ask. “I want to make a film for Grandad of all the places he’s been. Where exactly did we go on the island?”

“I haven’t agreed,” Jodie huffs.

Mum ignores her. “South Beach or was it East Beach?” Her eyes close, her forehead wrinkles. “I remember him talking about the deer that live there.”

“What about the deer?” Last year, when Grandad and I had been out in the boat and saw the fawn and the deer, he’d talked as if they had a history together. I don’t know how to put all the pieces together, but I’m sure the deer have something to do with the story he wanted to tell me. “Mum, what did he say?”

“Let me think …”

I squeeze her hands between mine. “Mum, you have to remember. It could be very, very important.”

14.

I MAKE HER A CUP OF TEA AND SIT WITH MUM ON the sofa.

“I’m not sure what I remember,” Mum says. “It was quite a few years ago.”

“Mum, pretend I’m doing an interview and I’ll ask questions. Maybe that will help you.”

“OK,” she says and leans back. “Ask away.”

“When did we go?”

She takes a moment, breathes a long breath through her nose and closes her eyes.

“You would have been about eighteen months old, so it was probably near the end of the summer holidays.”

“Was it sunny?”

She hesitates. “Yes, warm and breezy.”

“And we went on the ferry from the quay?”

“Yes. Oh yes, and we took a picnic with us … and a blanket … and a bucket and spade, for you. You were wearing flip-flops and they wouldn’t stay on your feet. Grandad carried you and the buggy …” She turns her head to me and opens her eyes. I know she sees Grandad as he was. “I’m always nervous crossing the gangplank and he was so much stronger back then.” I nod. “And you … you’ve never seemed to be afraid of anything when you’re around him.” I smile; I’m enjoying a memory of him.

I remember being in my cot, waking early, dawn breaking through the curtains. I stood up and rattled the bars and yelled for Grandad. I heard soft footsteps in the hall, the click of the door handle. I held out my arms, then I was up near the ceiling with Grandad. No, I never felt afraid around him.

Mum’s smiling. We turn on our sides so we’re facing each other.

“Where did we go when we got to the island, Mum?”

“South Bea

ch. Down the steps. Grandad was still carrying you. We had our picnic.”

“And then?”

“I think I lay there. Maybe snoozed … no, I read a book and you went paddling with Grandad. That’s right. He carried you a long way out to sea. I could hear you crying and he waved for me to come out.”

“Did you?”

“I hitched up my skirt and waded out!” She laughs and it’s nice because I can almost feel like I’m there too. “The water was only up to my knees, but I felt like I’d walked for a mile.”

“Why was I crying?”

“I don’t know.” She’s quiet for a moment. “I don’t think you cried for long.” She kisses me. “Grandad was talking to you while you were out there, telling you something that made you stop crying. You see, I’ve never had to worry about you. Not with Grandad around.”

I wonder what he’d said. He always knew what to say to make me feel better.

“What about the deer, Mum? What did he say about them?”

She closes her eyes again. “The deer?” I hear her breath. “He was talking about Grandma.” Her eyes open. “Actually, I think she was probably the one who had a soft spot for the deer. Yes, I remember now. I think something happened to the deer during World War Two and it took a while for the population to recover. I think he said they used to go out in the boat to check on them. I never saw them go though.”

“Did they go to Gorbreen or Furze Island?”

She frowns then shrugs. “You know, even when they were getting old, your grandparents were still like a couple of kids. Secretive and very sweet to each other.”

“They never took you with them?”

“No. I suppose it was just something they did together.”

“I wish I’d known Grandma.”

“Yes, I wish you had too.”

It’s quiet for a moment and I can tell she’s thinking about Grandma because her eyes and smile are soft.

“Mum, did Grandad ever tell you a special story about the deer or maybe about one important deer?”

“No, he didn’t.”

I roll on to my back. I think I’ve found a path back to Grandad, but I’m not sure what it means at all. Alzheimer’s is taking his memory away, but maybe I can find lots of clues to remind him.

“Mum? Grandad said he was saving a story to tell me.” I don’t know how to say the next bit, but Mum has already worked it out.

“You mean why didn’t he tell me?” She’s smiling and it’s OK. “That’s simple. He always had Grandma before you came along.”

Jodie comes in and sits between us and I can tell by the way she cuddles us both that she’s been listening.

“All right,” Jodie says. “Maybe I will let you come to the island with me, Hannah.”

“And maybe,” I say, “maybe we’ll find a whale too.”

15.

WE DON’T HAVE THE MONEY FOR A VIDEO CAMERA so Dad borrows an old one from someone he knows. Dad’s a bit funny about money at the moment because he says it’s taking a while to sort out Grandad’s savings to pay for him to be at the care home.

Jodie and I have a couple of days at home before we go to Furze Island and I try to think of the best way to film things. I want this to be special, to be just for Grandad.

Jodie helps me tape the camera to Dad’s hard hat, so that the camera is just above my eyes. Only the hat is too big and I have to keep pushing up the peak.

“Do I look stupid?” I say.

“I’ve spent ages doing this,” Jodie says. “So, no.”

When I walk out of the house, Linus and Josh are sitting on our wall. I haven’t seen them for a while.

“Why are you wearing a hard hat?” Linus says.

Josh looks up. “Is it raining frogs?”

And I have to say, “No, silly. I’m making a film.”

They inspect the camera and Josh smirks and says, “Your film’s not going to be very interesting.”

He crouches in front of me and looks up and waves and makes silly voices. Linus looks at my face and yanks Josh up by his T-shirt.

Josh says, “What?”

But Linus ignores him and says, “Do you want to borrow my scooter, Hannah?”

I grit my teeth because actually I want to punch Josh because I don’t like someone making fun of something important I’m trying to do. But instead I look at Linus and say, “What for?”

“Dunno,” he shrugs. “Maybe you could put the camera on it.”

“Then you could film people’s ankles,” Josh giggles.

“Shut up, Josh,” says Linus.

“Yeah, shut up,” I say and go back inside the house.

Jodie and I watch the film back and realise why Josh had said it wasn’t very interesting. The camera had slipped and I’d recorded my shoes and the pavement, and then Linus’s and Josh’s shoes and the pavement, and then Josh crouched there making stupid voices and noises, which is extremely dull and annoying. So it hasn’t really worked.

I have another think. Jodie helps me strap the camera with strong tape to an old baby harness round my chest. It feels right, like I’ll be recording things from my heart, which seems better than the one cold eye of the camera.

“Does this look stupid as well?” I say.

“No,” Jodie says, “not really.”

Then we realise we’ve put the lens cap somewhere and can’t find it, but Jodie says, “Just use this when you’ve finished,” which is a clean milk bottle top and some more tape.

I’m recording all our everyday things, trying to make all the solid things in our house seem as real on a screen to Grandad. I hope his eyes will be able to see more.

Jodie makes us lunch and afterwards we sit down to watch the recording of our house from my heart, and this is what we watch: boring cupboards in the kitchen and then my food on the plate and pieces of sausage disappearing over the top of the camera. And then we watch Jodie getting up from the other side of the table because she has finished her lunch, only you wouldn’t know it was her because it is just her middle and then her back.

“What’s that in my pocket?” Jodie says because we see the outline of something circular as she disappears off the screen.

Jodie feels in her back pocket. The lens cap! It makes me think about how the film shows us something from a bit earlier, something we hadn’t noticed at the time. And I wonder if you watched your whole day back, would you find all sorts of things?

Then we watch beans being pushed around with a knife and fork, and then the plate is carried into the kitchen and the beans scraped and we see them plop into the bin.

Jodie says, “I didn’t see you do that earlier.”

So I tell her the beans were nice, but there were too many, and remind her that my stomach is actually very small because it’s in proportion to the rest of me.

“I know,” she says. “I didn’t think I gave you too much.”

And then in the film I go over and put my plate in the sink and the picture goes black and the sound is muffled for ages because I was leaning against the sink and washing up.

“It’s not right,” I say. “It’s not the sort of film I want.”

“No,” Jodie says. “But it’s us doing ordinary things and that’s important for Grandad.”

I thought it would be easy to make a film, but it isn’t. And it’s hard to find things that stick out big and bright, full of the wonders we saw every day. It isn’t like how I remember things with Grandad.

“I thought the film would be about us, but we’re hardly in it at all,” I say.

“Maybe you should just hold the camera instead,” Jodie sighs. She is already bored.

The phone rings. One of Jodie’s friends. She sits cross-legged on the floor and flicks through a magazine while she talks.

I put the harness back on.

“I’m going out,” I say. Jodie waves, but she’s had enough now. “If I see Josh again and he says anything about me wearing a baby harness, I’m going to poke his eyes out.” Jodie

isn’t listening. “And if he laughs I’m going to kick his shins.” She nods.

I roll my eyes at her. “What?” she mouths.

“Nothing.”

I go outside to look for the birds. I try to fill the film with the things that might remind Grandad of us. Maybe then he’ll find us too.

16.

TODAY I’M UP IN GRANDAD’S BEDROOM TRYING something else. I’m pointing the camera through Grandad’s binoculars, which makes a circle on the film like a telescope, and I quite like that. I film the grey-green sea and Furze Island in the harbour and plenty of sky and the buildings and boats that look like toys from here.

Closer to our house I hear clip, clip, clip and point the camera at Mr Howard who is cutting his hedge and a lady walking past with her dog that looks anxious and yaps at him. And then the dog jumps to the side and barks as something silver flashes past. I’ve zoomed in too much and can’t tell what it is at first. I follow the silver flash and see Linus on the other side of the road with his scooter and he’s looking up at me.

“Are you going to be making a film today?” he shouts.

“I might be,” I say. “Where’s Josh?”

“What?” he says.

I realise I can hear him through the glass, but he can’t hear me and I wonder why that is. I think about shouting louder, but it’s no use.

“Come out,” Linus says, squinting up at me. “I can’t hear you.”

Jodie is leaning over the kitchen counter, talking on the telephone.

“I’m going out filming with Linus,” I say.

She nods and puts her hand over the phone and mouths, “Don’t go far.”

When I get outside, Linus sees the camera strapped to the toddler harness. I put my hands on my hips to dare him to say anything. But he doesn’t laugh.

A Horse for Angel

A Horse for Angel Harry and Hope

Harry and Hope The Riverbank Otter

The Riverbank Otter A Hundred Horses

A Hundred Horses The Midnight Foxes

The Midnight Foxes Jack Pepper

Jack Pepper The Secret Cat

The Secret Cat The Forever Whale

The Forever Whale